The Anglo-Irish Treaty 1 was the peace agreement that brought the Irish War of Independence to an end. The conflict had commenced on 21 January 1919 with the lethal attack on police in Soloheadbeg, Co. Tipperary. It was characterised on the Irish side by a campaign of guerrilla warfare and the creation of a system of government under Dáil Éireann to undermine the British regime. The fighting had grown in intensity until the truce of 11 July 1921.

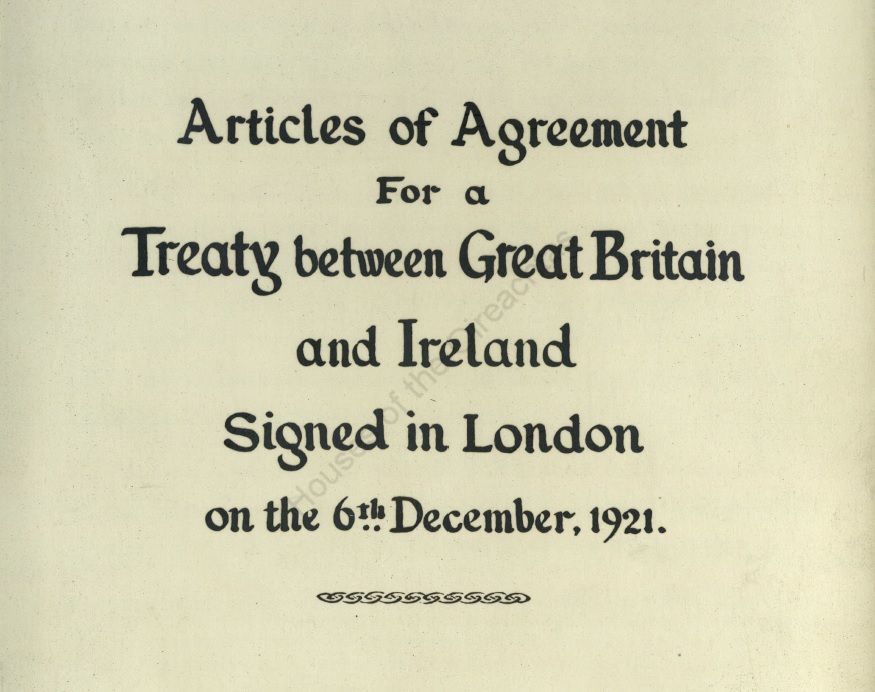

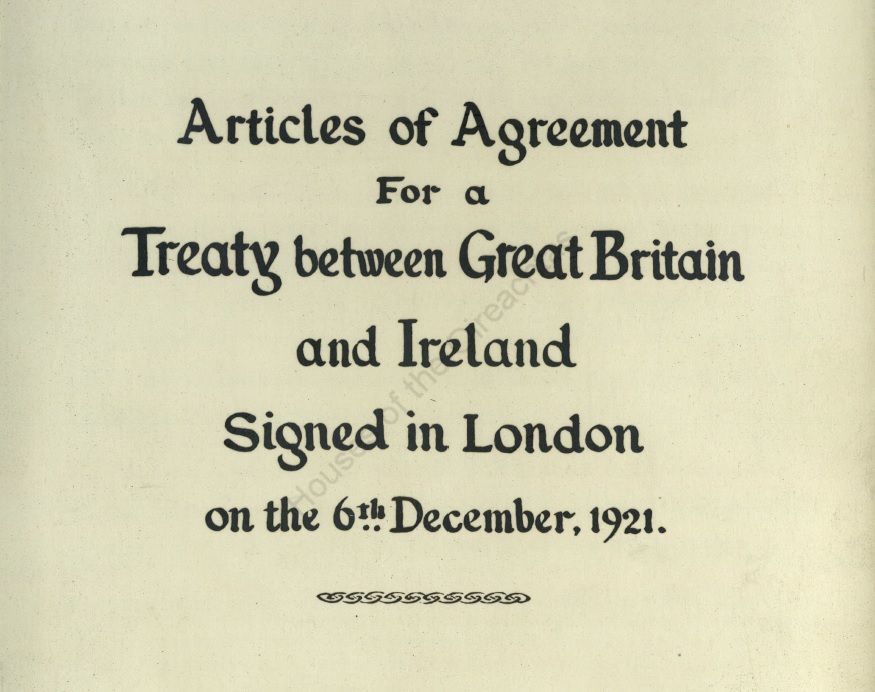

By any standards, the Treaty signed on 6 December 1921 was a landmark agreement in the history of the two islands. The inclusion of the word ‘Treaty’ in the title of the document connoted an agreement between distinct, established, equivalent juridical entities. Its supporters in the subsequent debate in Dáil Éireann argued that the word was proof that Ireland had achieved its goal of statehood separate from Britain.

Opponents of the Treaty disagreed. They argued that Ireland had been a separate entity since the Declaration of Independence at the first public sitting of Dáil Éireann on 21 January 1919, if not the declaration of the Republic on Easter Monday 1916. The fact that the text specified that the agreement was indeed ‘between Great Britain and Ireland’ marked the agreement out as having peculiar resonance, not just between but within the islands. No reference was made to Northern Ireland, although it had legally been in existence for a number of months at this point.

With the ratification and implementation of the accord Ireland joined the global state system. This was symbolised by its swift admission into the League of Nations. However, ratification of the Treaty also marked the descent into civil war, the bitter legacy of which has not yet been fully resolved 100 years on.

During the Treaty negotiations the Irish goal was to get the British to recognise the island of Ireland as an ‘external associate’, as opposed to a member, of the British Empire or Commonwealth. They wanted Ireland to have a republican form of government, with sovereignty derived from the people, recognising the Crown only as the symbolic head of Ireland’s political connection with the Commonwealth. The tactics used to achieve this end had two principal features. The delegates discussed and agreed lesser matters, such as finance, first and deferred issues of status and Crown until the latter part of the talks. They also positioned the delegation so that any breakdown in the talks could be focussed on ‘Ulster’ or ‘essential unity’ (that is, the incorporation of the six counties in some form within an overarching Irish state) and not on the Crown or status. The thinking behind this approach was that the British Government would not have support from domestic public opinion to resume their military campaign in Ireland in the former scenario but would in the latter.

The British were also content to defer discussion of the principal questions until later in the talks. When these questions could no longer be evaded, however, fundamental differences from the Irish position were immediately apparent. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was adamant that the British view of the Crown and Ireland’s membership of the Commonwealth had to be part of the final agreement.

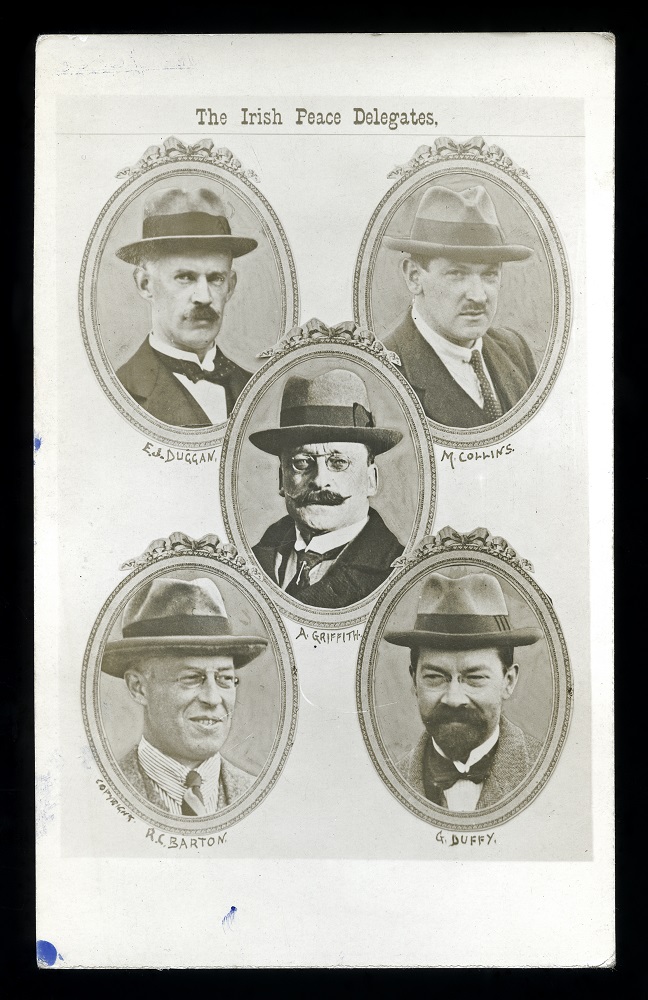

The Irish negotiating team, led by Arthur Griffith but not including the President of Dáil Éireann, Éamon de Valera 2 , handled the initial negotiations very well. In early November they were well positioned to ensure that the talks ‘broke on Ulster’ if an impasse was reached. Lloyd George, however, employed clever rhetorical footwork to reposition himself and introduced a proposal to redraw the boundary on the island by means of a ‘Boundary Commission’. Thus, he got Griffith, and through him the other Irish representatives, to commit to a solution that both recognised the Crown and acknowledged Ireland’s status as a new dominion of the Commonwealth but did not guarantee Irish unity. These were the key provisions of the Treaty signed on 6 December 1921.

The debate on the agreement at Westminster took place over three days and proceeded without any great difficulties. Nevertheless, Conservative members of the British negotiating team, notably Lord Birkenhead, were accused by the die-hard section of the party as having betrayed the party’s unionist traditions.

The debate in Ireland took longer and was more emotive and the division of opinion produced far greater political and human damage. The Treaty itself provided that the requisite sanction be obtained from ‘the members elected to sit in the House of Commons of Southern Ireland’ not Dáil Éireann, even though it was the latter assembly that had appointed the Irish negotiating team. But there was no doubt that the Dáil would indeed debate the text.

This debate took place between 14 December 1921 and 7 January 1922, with a break for Christmas and the new year. During the Treaty debate in Dáil Éireann those who supported the Treaty anchored their arguments for the most part in the concrete advantages offered by it, notably statehood and the evacuation of British forces from the new Irish Free State. They emphasised the threat that repudiation would lead to a renewed and destructive war. Those who opposed the Treaty focussed their attention on what they argued was the betrayal of the Republic. This, they argued, was implied in the acceptance of dominion status and of the Crown, the restrictions on Irish freedoms in such areas as defence, and the fact that the political border between north and south remained.

There was confusion in the minds of many as to the distinction between this new Provisional Government and the existing Dáil Executive. The latter was under the presidency of Griffith, following de Valera’s resignation in protest at the Treaty vote. This dual power period continued until the Third Dáil convened in the autumn of 1922. Both Collins and Griffith, along with a number of anti-Treaty republicans, had died in the meantime, casualties of the Civil War. The Third Dáil, elected earlier in the summer on a 26-county basis, confirmed William Cosgrave in his role as Head of Government.

The Irish Free State formally came into being on 6 December 1922, a year to the day after the Treaty had been signed. It did so minus the six counties of Northern Ireland. The government of Northern Ireland had already availed of a provision of the Treaty under which it was permitted to vote itself out of the Free State’s jurisdiction. From this point on, the Oireachtas as we now know it began to function. Dáil Éireann sat on 6 December and the new upper house, Seanad Éireann, met for the first time on 11 December 1922.

1 Otherwise known as the ‘Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland’ and occasionally the ‘Articles of Agreement.’ The text, as signed in the early morning of 6 December 1921, did not include the word ‘Treaty’ but rather was entitled ‘Articles of Agreement’. Later that morning, word was sent to the British delegation that the Irish wished for it to be included in the title and the British Cabinet meeting held at 12.30pm that day sanctioned the amendment. By this time, however, Eamonn Duggan had already departed London for Ireland with the only signed copy of the agreement (minus the reference to ‘Treaty’) kept by the Irish side. This was the copy handed by Duggan to President de Valera in Dublin that evening.

2 The other plenipotentiaries were Michael Collins, Eamonn Duggan, George Gavan Duffy and Robert Barton. Four others—Erskine Childers, Fionán Lynch, Diarmuid O'Hegarty, and John Chartres—served as secretaries to the delegation.